Interview with Thomas Olver: Moving Past ‘Patria’

2024/06/21

Euskara. Kultura. Mundura.

Thomas Olver completed his PhD in comparative literature at the University of Liverpool. His tesis, ‘Locating Memory in Contemporary Basque Literature: Moving Past Patria’, has become an essential reference for understanding how collective and personal memory are intertwined in the literary narratives of the Basque Country. His research won the most distinguished doctoral theses in Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian Studies, AHGBI Publication Prize 2024, in the United Kingdom.

Olver analyses how Basque authors Edurne Portela (‘Mejor la ausencia, 2017), Karmele Jaio (‘Aitaren Etxea’, 2019), Katixa Agirre (‘Atertu arte Itxaron’, 2017), Gabriela Ybarra (‘El comensal’, 2015) and Aixa de la Cruz (‘La línea del frente’, 2017) tackle the memory of the Basque conflict, highlighting the critical and diverse representation of historical memory. Their work challenges simplistic narratives and advocates for a more nuanced comprehension of history. This research not only provides critical insight into Basque literature, but also offers a robust theoretical framework for studying cultural memory in other regional literatures.

In this interview, Olver discusses his key discoveries and offers insights into the role of literature in shaping and conserving the collective memory of the Basque conflict.

Can you explain how your thesis deals with portraying the historical memory of the Basque conflict in modern literature?

My thesis analyses five novels by contemporary Basque women authors – Edurne Portela, Karmele Jaio, Katixa Agirre, Gabriela Ybarra and Aixa de la Cruz. – and focuses specifically on how they address the issue of memory in their work, especially as it relates to the legacy of the Basque conflict. Through analysing how these writers portray memory as inherently unstable and ambiguous, I aim to illustrate how they maintain a deeply critical stance towards the imposition of a definitive narrative on history. This critical perspective is pivotal in the ongoing "battle of narratives" that has contributed to significant divisions in both the Basque Country and Spain following ETA´s cessation of activities.

I propose that these novels resist the inclination to establish a singular truth regarding the past, as doing so tends to marginalise or disregard non-dominant voices and perspectives. Conversely, these works implicitly endorse modes of memory characterised by dialogue, diverse perspectives, the authors´ self-reflection, and a more intricate comprehension of the historical, social, and political backdrop within which the violence emerged.

What differences have you found between the narratives of Basque writers who experienced the conflict first hand and those who have approached it from a later perspective?

There are indeed significant differences. First, I would argue that one thing all these narratives have in common is the gradual reflection of their narrators regarding the positioning of their own perspectives on the past. This introspection both limits and moulds each person’s unique understanding of history.

If we consider for example ‘El comensal’ – a novel in which Gabriela Ybarra tries to understand the assassination of her grandfather ETA. Throughout the work, the author consistently emphasizes her own detachment from this traumatic incident, as she did not directly experience it. Ybarra creates a narrative tension between her deep desire to understand what it was like for her family to live through this trauma and the impossibility for her to overcome the distance that separates her from her grandfather´s death.

Regarding the narratives of women writers who directly lived through the conflict, while they may exhibit a more straightforward approach, these authors acknowledge implicitly that any viewpoint on the past is limited, understanding that each perspective is just one piece of a larger puzzle.

This is very clear in Edurne Portela’s ‘Mejor la ausencia’. In this work, the author selects a young girl as the narrator, whose childhood is shaped by the violence present in her surroundings, both within and outside the home. By opting for this narrator, who struggles to grasp the violence enveloping her, Portela compels us to view the past through a restricted and fragmented perspective. At the end of the novel, the narrator, now grown, contemplates her own history and comes to the realisation that there is still much she has yet to comprehend. This understanding leads her to realise that closing these gaps in her knowledge of the past can only be achieved by actively seeking out and listening to alternative viewpoints.

Have you identified any shared elements in the various works you have studied, and have you noticed specific narrative techniques employed by the authors to address intricate topics like conflict and memory?

I’ve already discussed the introspective nature of these works, and I believe that in every novel I have examined, there is a distinct focus on the writer´s role. This includes how the writer approaches the past within their narrative, how they situate themselves concerning this past and violence, and how they acknowledge the boundaries of their own perspective on events of the past. In all of these books, the narrator-authors constantly emphasise the artificiality of their portrayals of history: they frequently reflect on the process of writing, grappling with the elusiveness of complete historical understanding, and recognising the importance of exploring and envisioning alternate perspectives.

Ybarra, for example, uses a wide range of literary styles, mixing tropes of detective fiction with fantastical elements to tell her grandfather´s story, acknowledging that it is nothing more than a fictional reinvention.

Katixa Agirre and Karmele Jaio employ fragmented structures to illustrate how the past is composed of diverse narratives, perspectives, and a multitude of voices. In short, what they make clear to the reader is that understanding the past is an ongoing process that must be wary of "overarching narratives", prioritizing the incorporation of diverse voices, all while acknowledging the limited viewpoint inherent to each perspective.

Are there any notable similarities or differences in how the Basque conflict is portrayed in literature as opposed to other historical conflicts in Europe or globally?

I was born in Belfast, so the conflict in Northern Ireland has been the most immediate parallel for me. While I didn´t experience the most turbulent years of that conflict, I am acutely aware of its deep influence on the society I was raised in. Therefore, I have always been intrigued by exploring how individuals comprehend a past they didn´t directly experience but that nonetheless significantly shaped their lives.

The body of literature concerning the conflict in Northern Ireland is extensive and remarkably varied. It is somewhat difficult to speak in general terms about it. But it is curious to note that, to the best of my knowledge, no work attempts to offer us a comprehensive and all-encompassing portrayal of the conflict, which, in my opinion, differs from what has been witnessed in Spain with the publication of Fernando Aramburu´s ‘Patria’.

´Patria´ TV show (2020, Aitor Gablibondo)

I would argue that, on the contrary, there has been a preference for more intimate narratives, which give voice to more marginalised perspectives and illustrate how so many people were caught up in the violence that afflicted their communities. Several authors have also used quite radical styles to represent our past, such as Anna Burns´ ‘Milkman’, which, which, through at times surreal prose, articulates the teenage girl´s perspective on conflict while living in Belfast. Jan Carson´s ‘The Fire Starters’ is noteworthy for its innovative use of magical realism to delve into how the legacy of conflict impacts the youth in present-day Belfast.

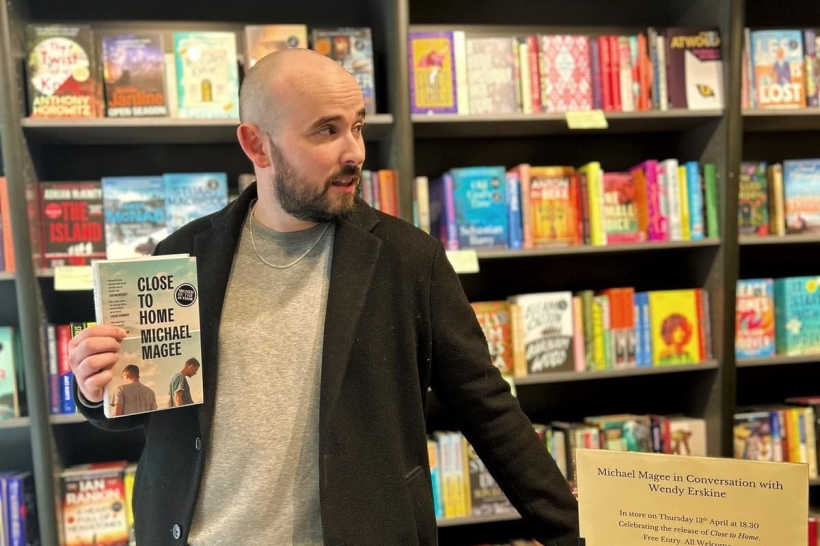

In recent years, a number of novels have been published that explore how the deep scars of the conflict still linger to this day. One book that I strongly recommend and that, in my view, captures this influence effectively is Michael Magee´s ‘Close to Home’. It shows the trauma that many families in Northern Ireland have inherited and the difficulties of talking openly and the ongoing challenges of openly discussing a past that still evokes profound pain for many individuals. But what he also illustrates very effectively is how the optimism and hope that characterised the late 1990s, following the signing of the peace accords, have gradually faded. His novel conveys the profound disillusionment experienced by many due to the ongoing inability to address not just the repercussions of the past but also the socio-economic challenges inherited from the conflict. These issues have deprived a new generation of young individuals of opportunities for the future.